Dad used to take me to the NCO Club with him on Saturday afternoons after we had finished our work in the yard of our new home and on any other chores my Mother had dreamed up for us to do. At the Club, I was introduced to my first mixed drink - a Roy Rogers - and to my father's friends, who found in me a new and receptive audience for their reminisces, and who, after a few beers and several mixed drinks of their own - regaled me with some fascinating stories about World War II. Since we had been stationed in Japan in the mid-'50s, I already had a well- developed interest in the War and, as it turned out, one of my Father's friends told me of how he had survived the Bataan Death March which followed the fall of the Philippines in April of 1942 and prompted General Douglas MacArthur's famous quote "I shall return." What I remember most about these stories was the sing-song nature of the Japanese speech patterns. "Iti eades, boy-san tounae day-sho." It is especially ironic at how beautiful the rhythms are and how horrid the images are expressed in the language. I am not sure how those words are actually spelled in the Japanese language or what they mean but this is how they sound phonetically to my ear. Beautiful rhythms mixed in with the horrific nature of the stories actually expressed by those rhythms.

Dad used to take me to the NCO Club with him on Saturday afternoons after we had finished our work in the yard of our new home and on any other chores my Mother had dreamed up for us to do. At the Club, I was introduced to my first mixed drink - a Roy Rogers - and to my father's friends, who found in me a new and receptive audience for their reminisces, and who, after a few beers and several mixed drinks of their own - regaled me with some fascinating stories about World War II. Since we had been stationed in Japan in the mid-'50s, I already had a well- developed interest in the War and, as it turned out, one of my Father's friends told me of how he had survived the Bataan Death March which followed the fall of the Philippines in April of 1942 and prompted General Douglas MacArthur's famous quote "I shall return." What I remember most about these stories was the sing-song nature of the Japanese speech patterns. "Iti eades, boy-san tounae day-sho." It is especially ironic at how beautiful the rhythms are and how horrid the images are expressed in the language. I am not sure how those words are actually spelled in the Japanese language or what they mean but this is how they sound phonetically to my ear. Beautiful rhythms mixed in with the horrific nature of the stories actually expressed by those rhythms.It was the coincidence 0f a Zippo lighter appearing in both of our recollections twenty years apart that appealed to me and was the most telling aspect of both stories. I had seen advertisements in a stack of old Field and Stream magazines at my barber shop that highlighted the durability of the Zippo lighter. Apparently, they were in the midst of an ad campaign about the unusual places that Zippos happened to turn up and one ad featured a lighter that was still functioning after it was found in the stomach of a dead grizzly bear and another one that had - to my surprise - survived the Bataan Death March itself. This, of course, dovetailed nicely with the story I had been told at the Club by one of my Father's friends about his survival and his Zippo's survival of long odds in the almost impossible situation on the Bataan peninsula in 1942 and how it was itself an ironic commentary on a story of survival at all costs. What I most wonder, however, is how many Zippos actually survived Bataan or if the story itself was apocryphal . Truth and beauty do not always intersect.People who write about the soldiers involved in warfare always have uncovered the most horrible things that the pressure cooker of war produce in the people who fight in them. As a person who has always had an interest in such things I always remember that as the weapons of war devoloped so did the carnage produced by them. I remember a recurring image of a soldier in the trenches not being able to fall to the ground after being shot several times. He appeared to be strung up in mid-air and looked for all the world like a marionette, an effect that can only be produced by machine-gun fire - a weapon that was introduced to warware around the turn of the 20th century just in time for World War I. It was obviously a popular image as I saw it reported as both historical fact and as a fictional construct several times. I didn't know whether it actually happened but it was very vivid in it's own right.

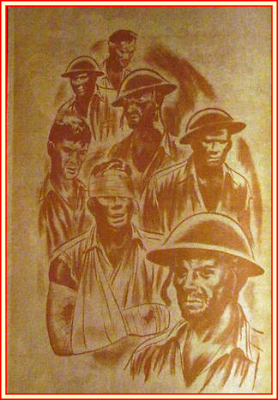

" We were outnumbered better than five-to-one, with more Gink soldiers pouring in all the time and we realized that it was going to be either surrender or die. The indigenous population, which numbered some ten thousand in all, were caught between us and the enemy and we decided that surrendering to anybody who happened to come around was probably the best thing for us to do because the Japs had to get us out of there so their own people could continue to move in and prepare for the big assault on Corridor, the stronghold just off our coast. We were just in the way which was a new feeling for somebody who considered himself a pretty fair rifleman and his country the only invincible power on earth. We were at the base of Mount Cabcaben in nearly impenetrable terrain when we started out on our long journey which came to be called The Bataan Death March and, God bless us, it was aptly named. The first thing they wanted us to do was get assembled at a place called Balanga. We were to get there on our own from wherever we happened to find ourselves but we had no food or water, and were completely exhausted and it was just starting to occur to us that our nightmare, far from winding down, was just beginning. There were only nine of us left who had survived the final assault at Mount Cabcaben and we began walking across a pre-cleared firing area toward Balanga as it was only twelve or fifteen miles from where we were."

" We were outnumbered better than five-to-one, with more Gink soldiers pouring in all the time and we realized that it was going to be either surrender or die. The indigenous population, which numbered some ten thousand in all, were caught between us and the enemy and we decided that surrendering to anybody who happened to come around was probably the best thing for us to do because the Japs had to get us out of there so their own people could continue to move in and prepare for the big assault on Corridor, the stronghold just off our coast. We were just in the way which was a new feeling for somebody who considered himself a pretty fair rifleman and his country the only invincible power on earth. We were at the base of Mount Cabcaben in nearly impenetrable terrain when we started out on our long journey which came to be called The Bataan Death March and, God bless us, it was aptly named. The first thing they wanted us to do was get assembled at a place called Balanga. We were to get there on our own from wherever we happened to find ourselves but we had no food or water, and were completely exhausted and it was just starting to occur to us that our nightmare, far from winding down, was just beginning. There were only nine of us left who had survived the final assault at Mount Cabcaben and we began walking across a pre-cleared firing area toward Balanga as it was only twelve or fifteen miles from where we were."  "Once I saw one of them, a Filipino, eating the meat of a python. I never ate python and I never ate monkey after the first time. Lizard you can keep down but monkey-meat is like eating something that came jumping and swinging out of hell itself and I was willing to go just so far with the max stress routine. The other thing was malaria, which everybody had. But it really wasn't too bad under the circumstances as we were able to get some sugar cane from the fields which alleviated the symptoms to some extent and what streams there were to drink from probably made us prone to dysentery but most of us were suffering from it in the first place and we had to have water. We had a colonel with us and he had a pass that some Gink officer had given him when we surrendered. He showed this pass to anybody we ran into on the road and they didn't give us too much trouble. They searched us and took rings and watches and anything else they could find, but I managed to hold on to my Zippo lighter, which twenty years later was part of an ad campaign I saw that they were running: THIS ZIPPO SURVIVED THE BATAAN DEATH MARCH. I managed to keep it hidden in the toe of my boot and held on to it for the rest of the war. (I have it to this day). We got to Balanga that night. We had covered the distance in one day with hardly any strain. When we arrived we heard the enemy had executed about four hundred indigenous military personnel, officers and noncoms. The Filipinos were on their way to Balanga like the rest of us when they were stopped by some Japs who were part of an aftermath reaction force. They let everybody go except the officers and noncoms, who were lined up in several columns and then tied together at the wrists with telephone wire. Then they took out their swords and bayonets and killed them.

"Once I saw one of them, a Filipino, eating the meat of a python. I never ate python and I never ate monkey after the first time. Lizard you can keep down but monkey-meat is like eating something that came jumping and swinging out of hell itself and I was willing to go just so far with the max stress routine. The other thing was malaria, which everybody had. But it really wasn't too bad under the circumstances as we were able to get some sugar cane from the fields which alleviated the symptoms to some extent and what streams there were to drink from probably made us prone to dysentery but most of us were suffering from it in the first place and we had to have water. We had a colonel with us and he had a pass that some Gink officer had given him when we surrendered. He showed this pass to anybody we ran into on the road and they didn't give us too much trouble. They searched us and took rings and watches and anything else they could find, but I managed to hold on to my Zippo lighter, which twenty years later was part of an ad campaign I saw that they were running: THIS ZIPPO SURVIVED THE BATAAN DEATH MARCH. I managed to keep it hidden in the toe of my boot and held on to it for the rest of the war. (I have it to this day). We got to Balanga that night. We had covered the distance in one day with hardly any strain. When we arrived we heard the enemy had executed about four hundred indigenous military personnel, officers and noncoms. The Filipinos were on their way to Balanga like the rest of us when they were stopped by some Japs who were part of an aftermath reaction force. They let everybody go except the officers and noncoms, who were lined up in several columns and then tied together at the wrists with telephone wire. Then they took out their swords and bayonets and killed them. We heard they beheaded most of them. They didn't use any guns and it took about two hours to kill all four hundred. Must have been something to see. We heard it was revenge for something the indigenous personnel had done, but nobody knew what. To tell you the truth I don't think anybody cared. In the situation we were in, which was one of total, complete and utter heat and boredom, wondering what manner of crawling scabby insect we were going to dine on next, the fact of four hundred headless Filipinos was a topic for pleasant clubhouse gossip, something to discuss briefly in mild awe and almost admiration for the Ginks for at least having a sense of spectacle and to be grateful for in a way because it took our minds off our own problems. But Balanga itself turned out to be unforgettable. Thousands of men were pouring into the town, from every direction, particularly from the South.

We heard they beheaded most of them. They didn't use any guns and it took about two hours to kill all four hundred. Must have been something to see. We heard it was revenge for something the indigenous personnel had done, but nobody knew what. To tell you the truth I don't think anybody cared. In the situation we were in, which was one of total, complete and utter heat and boredom, wondering what manner of crawling scabby insect we were going to dine on next, the fact of four hundred headless Filipinos was a topic for pleasant clubhouse gossip, something to discuss briefly in mild awe and almost admiration for the Ginks for at least having a sense of spectacle and to be grateful for in a way because it took our minds off our own problems. But Balanga itself turned out to be unforgettable. Thousands of men were pouring into the town, from every direction, particularly from the South.

They put some of us in pastures.

Others they kept in small yards behind barbed wire. We were all jammed together and it was impossible to sit down and the whole town smelled of defecation. The whole town! We were told to use the ditches to do our business in but they were so full of dead bodies that the smell of the dead and dying kept most of us away. Men with dysentery couldn't control themselves and had to defecate where they stood. Others just fell down and died. All this time in Balanga standing in the pasture and later burying some of the dead I tried to take my mind off of our situation and think of my wife and all I could bring to mind was a scene from our wedding day: we were standing on the lawn of my parents home at Old Kinderhook

Others they kept in small yards behind barbed wire. We were all jammed together and it was impossible to sit down and the whole town smelled of defecation. The whole town! We were told to use the ditches to do our business in but they were so full of dead bodies that the smell of the dead and dying kept most of us away. Men with dysentery couldn't control themselves and had to defecate where they stood. Others just fell down and died. All this time in Balanga standing in the pasture and later burying some of the dead I tried to take my mind off of our situation and think of my wife and all I could bring to mind was a scene from our wedding day: we were standing on the lawn of my parents home at Old Kinderhook in northern New Jersey, just across the river from New York city, a small group of musicians clustered off to our left playing something romantic by one of the Dorsey brothers and that conjured up a modicum of sanity in a world gone insane : my home and bed, my beautiful wife's hair and lovely hands, but that image kept drifting away and I was too numb or, God help me, unfeeling to care really whether I could bring it back up but still she shimmered there, an image of loveliness standing alone half-profile, in a dim room like a Madonna on a Catholic medallion. Then she and the lawn and the musicians morphed into a horrific scene of men burying the dead, maggots and torn flesh everywhere, the smell of death overwhelming everything and then, abruptly, it all faded away and we were on the move again and the Japs were giving us rice to eat and sending us north but there were guards this time. We continued walking northward to a place called Orani. We saw a lot more corpses on the road and some indigenous noncombatants gave us more food and we drank polluted water from streams or puddles or out of leaves or whatever else could hold water. We weren't supposed to break ranks but we did anyway. We had to have water. It was worth the chance, no two ways about it. A lot of men were shot or bayoneted getting water. One of the guards was singing a song, walking along beside us in the hot sun. A sergeant named Ritchie, a demo expert with one of the anti-transit security outfits, broke ranks then and jumped the guard from behind and knocked his weapon into a ditch. Then he straddled the guard and started tearing at his throat. I don't think he particularly wanted to kill the guard. He just wanted to get inside him, open him up for inspection. Then a Jap soldier came trotting up the line and bayoneted Ritchie in the back.

in northern New Jersey, just across the river from New York city, a small group of musicians clustered off to our left playing something romantic by one of the Dorsey brothers and that conjured up a modicum of sanity in a world gone insane : my home and bed, my beautiful wife's hair and lovely hands, but that image kept drifting away and I was too numb or, God help me, unfeeling to care really whether I could bring it back up but still she shimmered there, an image of loveliness standing alone half-profile, in a dim room like a Madonna on a Catholic medallion. Then she and the lawn and the musicians morphed into a horrific scene of men burying the dead, maggots and torn flesh everywhere, the smell of death overwhelming everything and then, abruptly, it all faded away and we were on the move again and the Japs were giving us rice to eat and sending us north but there were guards this time. We continued walking northward to a place called Orani. We saw a lot more corpses on the road and some indigenous noncombatants gave us more food and we drank polluted water from streams or puddles or out of leaves or whatever else could hold water. We weren't supposed to break ranks but we did anyway. We had to have water. It was worth the chance, no two ways about it. A lot of men were shot or bayoneted getting water. One of the guards was singing a song, walking along beside us in the hot sun. A sergeant named Ritchie, a demo expert with one of the anti-transit security outfits, broke ranks then and jumped the guard from behind and knocked his weapon into a ditch. Then he straddled the guard and started tearing at his throat. I don't think he particularly wanted to kill the guard. He just wanted to get inside him, open him up for inspection. Then a Jap soldier came trotting up the line and bayoneted Ritchie in the back. When we got to Orani it stank even worse than Balanga. Just outside the town though, about a mile outside, I saw something so strange I thought it might be a vision, something brought on by the hunger and malaria. Attached to some trees at the edge of a field were two swings, obviously homemade, just boards and ropes fastened to tree limbs. Sitting on one of the swings, was what I thought was a Jap soldier but maybe it was the glare of the sun or maybe just the distance but he seemed to be a very old man, almost ancient. He wasn't wearing a uniform so I couldn't tell if he was an officer or not. You could always tell a Jap officer from other soldiers because, as a class, officers were significantly taller then the men they commanded. He was

When we got to Orani it stank even worse than Balanga. Just outside the town though, about a mile outside, I saw something so strange I thought it might be a vision, something brought on by the hunger and malaria. Attached to some trees at the edge of a field were two swings, obviously homemade, just boards and ropes fastened to tree limbs. Sitting on one of the swings, was what I thought was a Jap soldier but maybe it was the glare of the sun or maybe just the distance but he seemed to be a very old man, almost ancient. He wasn't wearing a uniform so I couldn't tell if he was an officer or not. You could always tell a Jap officer from other soldiers because, as a class, officers were significantly taller then the men they commanded. He was

looking at us, gliding very slowly on the swing a few inches forward, then a few inches back, his long legs just barely scraping the ground, looking at us and singing a song. At first I hadn't realized he was singing but now I could hear it coming across the field, a slow and what seemed a very sorrowful song. Maybe it was my imagination and maybe just my ignorance of the language but it seemed to be the same song the guard was singing before Ritchie jumped him and got killed for his troubles. And he just sat there, moving a few inches either way, singing that beautiful slow song and his hands loosely gripping the ropes along both sides of his head. If it was a vision, then it was a mass vision because all of us looked that way as we went along the road. But nobody said anything. We just looked at him and listened to the song. A little ways further on we passed one of the village pacification centers set up by Tech II and Psy Ops before the enemy terminated the whole concept. We were only in Orani about a day and then we walked to a depot of sorts in a larger town a little farther north called San Fernando, where they stuffed us in a warehouse. There were thousands of us in there, crushed and elbowing and going out of our minds. Nobody could sleep. We were all locked together and the stink was worse than ever because we were indoors. From there we walked to a rail center where they had trains waiting for us. Some of us were given food here and some weren't. We all looked forward to the trains, some dim and still functioning part of our minds thinking of God knows what childhood times we had spent on trains, the Twin Cities Zephyr if you were from the Midwest, or the San Francisco Chief or Afternoon Hiawatha if you were from the West;

some dim vision of going across the Great Plains on a Union Pacific train and everything is vast and wild and mysterious because you were only ten years old and America seemed as wide as all the world and twice as invincible. We looked forward to the trains but we should have known better by this time. They put us in boxcars. Whatever position you found yourself in when you were pushed into the boxcar, that was it for the whole trip. There were no windows and the doors were closed. It was the warehouse again, this time on wheels. A few minutes after the train started, somebody began to moo. That set us off. Soon we all began mooing and snorting, making noises like sheep, cows, horses, pigs. The Psy Ops people never told us about this kind of environmental reaction. Nobody laughed. We weren't fooling around. This was no comic celebration of the indomitable human spirit. No protest against inhumanity. We were cattle now and we knew it. We were merely telling ourselves that we were cattle and we shouted moo and baa in absolute seriousness and total overwhelming self-hatred. We were livestock now. How could anyone deny it? What else could we be but livestock, locked up as we were in boxcars and stepping in puddles of our own sick liquid shit. The ride seemed to take years. It seemed a trek across Asia. When, at last, we were all off the train we walked to the POW camp the Japanese had set up at what used to be Camp O'Donnell but we called it Fort Hirohito, where they processed us with one of our own incremental mode simulators. The march was over and I tried to get back to the small white beauty of my wife. But I had trouble returning. It was April and it was hot, the dawning of springtime in my part of the world but obviously not here, and it was odd that it brought with it a jumbled group of recurring musical images for reasons I couldn't envision, but there was our neighbor, Harkavy, who we called "the country squire", drinking Jack Daniel's on the rocks, decked out in his star-spangled pajamas like it was the 4th of July and playing his fiddle like a damned fool. And there was my mother dusting the piano in the old house like a Pharaoh's widow come to clean the tomb in preparation for some momentous occasion. And there were the musicians again milling about on the front lawn, strangely tinkling away and the minister and guests and our wedding taking place in the background. But it was all fading away in a disjointed jumble of sights and sounds in some dark part of my mind and I had to get back there because it was in Balanga that they forced us to bury the dead.

some dim vision of going across the Great Plains on a Union Pacific train and everything is vast and wild and mysterious because you were only ten years old and America seemed as wide as all the world and twice as invincible. We looked forward to the trains but we should have known better by this time. They put us in boxcars. Whatever position you found yourself in when you were pushed into the boxcar, that was it for the whole trip. There were no windows and the doors were closed. It was the warehouse again, this time on wheels. A few minutes after the train started, somebody began to moo. That set us off. Soon we all began mooing and snorting, making noises like sheep, cows, horses, pigs. The Psy Ops people never told us about this kind of environmental reaction. Nobody laughed. We weren't fooling around. This was no comic celebration of the indomitable human spirit. No protest against inhumanity. We were cattle now and we knew it. We were merely telling ourselves that we were cattle and we shouted moo and baa in absolute seriousness and total overwhelming self-hatred. We were livestock now. How could anyone deny it? What else could we be but livestock, locked up as we were in boxcars and stepping in puddles of our own sick liquid shit. The ride seemed to take years. It seemed a trek across Asia. When, at last, we were all off the train we walked to the POW camp the Japanese had set up at what used to be Camp O'Donnell but we called it Fort Hirohito, where they processed us with one of our own incremental mode simulators. The march was over and I tried to get back to the small white beauty of my wife. But I had trouble returning. It was April and it was hot, the dawning of springtime in my part of the world but obviously not here, and it was odd that it brought with it a jumbled group of recurring musical images for reasons I couldn't envision, but there was our neighbor, Harkavy, who we called "the country squire", drinking Jack Daniel's on the rocks, decked out in his star-spangled pajamas like it was the 4th of July and playing his fiddle like a damned fool. And there was my mother dusting the piano in the old house like a Pharaoh's widow come to clean the tomb in preparation for some momentous occasion. And there were the musicians again milling about on the front lawn, strangely tinkling away and the minister and guests and our wedding taking place in the background. But it was all fading away in a disjointed jumble of sights and sounds in some dark part of my mind and I had to get back there because it was in Balanga that they forced us to bury the dead.  It was in Balanga that they forced us to bury the dead. It was in Balanga that they forced us to bury the dead and I was throwing dirt onto the body of a Filipino when he suddenly moved. Poor little blood-faced indigenous Filipino soldierboy. When he started to rise from the ditch. Dozens of dead men around him covered already with maggots, completely covered so that the ground, the earth, seemed to be moving, rotting bodies everywhere and the whole saddle trench about to erupt. When he lifted himself on his elbow. I dropped my shovel and leaned way over the edge of the trench, all those billions of ugly things swarming into the mouths of my dead buddies and their dead buddies and their buddies' buddies and the tough-little brown-little indigenous military personnel. When he tried to extend a hand to me. I leaned way down and then felt something jab me in the ribs. It was a guard jabbing me with his bayonet in a light, casual, condescending and almost upper-class manner like a bloody British officer of the 11th Light Dragoons poking an Indian stable boy with his riding crop. When he tried to rise. I pointed to him, trying to rise, and then the guard did some pointing of his own. He pointed his bayonet at the shovel on the ground and then at the boy in the ditch. It was rather a deft piece of understatement, I thought. He wanted me to bury the little wog anyway."

It was in Balanga that they forced us to bury the dead. It was in Balanga that they forced us to bury the dead and I was throwing dirt onto the body of a Filipino when he suddenly moved. Poor little blood-faced indigenous Filipino soldierboy. When he started to rise from the ditch. Dozens of dead men around him covered already with maggots, completely covered so that the ground, the earth, seemed to be moving, rotting bodies everywhere and the whole saddle trench about to erupt. When he lifted himself on his elbow. I dropped my shovel and leaned way over the edge of the trench, all those billions of ugly things swarming into the mouths of my dead buddies and their dead buddies and their buddies' buddies and the tough-little brown-little indigenous military personnel. When he tried to extend a hand to me. I leaned way down and then felt something jab me in the ribs. It was a guard jabbing me with his bayonet in a light, casual, condescending and almost upper-class manner like a bloody British officer of the 11th Light Dragoons poking an Indian stable boy with his riding crop. When he tried to rise. I pointed to him, trying to rise, and then the guard did some pointing of his own. He pointed his bayonet at the shovel on the ground and then at the boy in the ditch. It was rather a deft piece of understatement, I thought. He wanted me to bury the little wog anyway."